Breeding on Paper

A debate on EBVs has been raging in the Scottish Farmer. Accurate, objective or reasoned letters must be too boring to print given the polarity of much seen. The “pros” are characterised by missionary zeal, the “antis” are reactionary and conservative.

Who has the moral high ground?

Unless you understand BLUP you won’t understand EBVs. BLUP is a statistical model for the prediction of random effects. If you need to know more about BLUP have a read of the appendix below.

Problems with EBVs

1 Management.

BLUP works best if all stock in a breed were recorded and managed in the same way. This doesn’t (can’t) happen in practice. BLUP tries to eliminate the effect of management, whilst paradoxically the majority ram and lamb producers use manage their flocks to optimise production.

BLUP works on management groups. If you give the top section of the group preferential treatment and the bottom a raw deal, it can skew the figures in favour if the top animals quite dramatically. To get really good figures you need the odd pathetic lamb.

2 cross breeding

It’s only pedigree females that tend to be recorded. Commercial females (with the exception of some composite pedigree mongrels) are not. How can you chose a tup on figures if you don’t know the figures of your ewes?

3 Who sets the parameters?

What you get out of BLUP not only relies on what you put in, but also how you set the parameters. In sheep it was designed to breed fat off native breeds. The same parameters applied to continental breeds led to farmers being unable to finish lambs out of supposedly high genetic value tups, especially out of mule ewes.

Then you have sheep breeding companies developing composites recorded to their own specific index. Who knows if those figures mean anything at all as there are no comparators bred by anyone else.

4 what is and is not recorded.

Only certain traits are recorded. Specifically in sheep, structural matters are not recorded. This can lead to high index animals being poor specimens, whether in terms of specific breed points or character, or generally.

EBVs concentrate on data from ultrasound scanning of the loin muscle and fat. It’s the depth of muscle that’s recorded. The deepest muscle may not necessarily indicate most volume of eye muscle. Also there is no EBV for eating quality. Even with CT scanning of the hind quarter, which has balanced some of the extreme results from ultrasound only, we do not know if we are breeding sheep with more muscle, but that nobody wants to eat. Similarly, the fat measure is of fat on the loin, not marbling within the muscle.

5 data overload

Another paradox is that if you record few traits you can get an overall index figure which is easily understandable, but lacks subtlety. Record a lot of traits then you get an overall index which is sophisticated to the point of being almost meaningless. So many trait permutations could lead you to the same index but the sheep would be vastly different.

6 farmers don’t get it.

When the Welsh Government were giving out vouchers for recorded tups I spent a lot of time trying to explain EBVs. I’m not sure if I was still talking now three years later I could get people to understand it fully.

7 take up

Without doubt, this is the main problem. Not enough stock are recorded. That means that despite all of the boffins’ assurances and trial work it’s questionable which of these would perform better in the field:

A – a high index high accuracy tup

B – a lower index tup – if that index is lower as a result of low accuracy due to a lack of connectivity with recorded stock

C – a completely unrecorded tup.

EBVs tell you that it’s less likely B’s progeny would do better than A’s, but that it’s not impossible. EBVs can’t tell you anything about ram C.

8 genomic breeding values

And just when you thought progress was being made, somebody comes up with a DNA test to predict performance. Instead of replacing EBVs however it’s proposed that these tests will be used to prove the validity of EBVs. That sounds like the recording industry in full self preservation mode.

9 a self fulfilling prophesy

The top index sheep are bred on very narrow lines to boost accuracy. BLUP likes accuracy, and if a lamb with high accuracy performs to the upper end of what is expected of it compared with its peers it will have good figures, even if it’s a relatively poor lamb on any other measure.

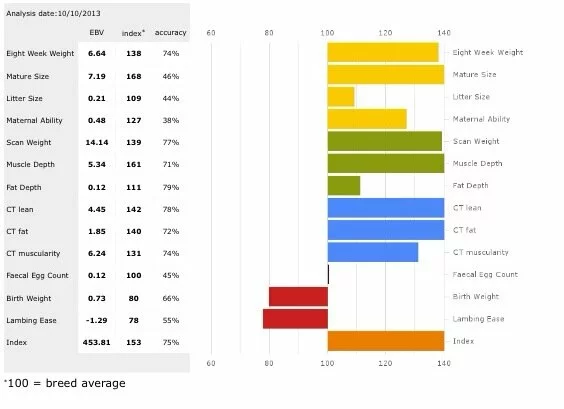

Look at this EBV chart:

It seems impressive. Yet at 21 weeks this lamb weighed less than 50kg (poor), had 30mm eye muscle (poorer) and just over 1mm fat (even poorer). Not fantastic in actuality by any means yet it is within the top 1% index in the country.

10 fiddles.

This dominates the debate on EBVs. The breeder is responsible for the vast majority of data input. The system is therefore subject to the risk of abuse. However this is not my main problem, as the man with his boot on the scale with his best lamb is kidding himself. There is a self righting mechanism within BLUP which will find him out. Is a flock with high accuracy in their ewes buy the tup his figures will drop like a stone when his lambs are recorded.

So…should you record your sheep?

Yes, absolutely. There is no doubt that this is the way things are going. There are two ways of getting your accuracy figures up – buy high index tups or record your ewes. The sooner you start recording your lambs the quicker you’ll get to the second and third recorded generation which will see your accuracies jump up. That’s a lot less risky in terms of maintaining type and character than the first option.

Because, if you go for the quick fix, and breed them on paper, you’d better prepare to sell them by post…

E.B. Reaves.

Saving...

Saving...

Add a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.